The Politics of “the Gospel”

May, 2024

On Jan. 6 when they stormed the US Capitol, some carried crosses, flags with Christian messages, and signs with bible verses on them, making their political desires into a religious crusade. But this was not new or surprising. All my life I’ve known right-wing conservatives to be devout Evangelical Christians whose politics were inextricably linked to their version of the faith. For the first half of my life, I heard the diatribes from the pulpits against “godless Communism.” Communists, after all, were atheists, anti-god, and anti-church. They imprisoned pastors, they tortured people for their faith. I read books about bible smugglers who risked everything to nurture the faith of those poor souls who found themselves behind the “Iron Curtain.” How could you be a Christian and not understand your faith to involve the politics of opposing Communism?

Back then, growing up in my fundamentalist home, I was too young to know about all the things my “Christian” nation was doing around the world to help God with His anti-Communist agenda: assassinating (or attempting to) foreign dictators, sponsoring coups, invading little nations, turning a blind eye to apartheid and human rights abuses, death squads, disappearances, and dirty wars. We knew that Communists wanted to gobble up the world, that the dominos would fall, and that the Christian West could recede into a corner of persecuted insecurity. Perhaps we would end up like the early Roman Christians, furtively meeting in the catacombs and making secret fish signs in the sand with our feet to identify our comrades? (You probably had to grow up in my subculture to understand that reference). Communists were anti-God; how could God’s A-team be non-politically neutral?

So, the cross and the flag that co-mingled in the mobs on Jan. 6 were neither new nor unusual. The new part was that the champion they were there to enthrone was such a non-religious, immoral man. He famously did not even know how to say “Second Corinthians” as any child of Sunday School did. When he held up a bible in that silent scene in front of a church that he never attended, he didn’t notice it was upside down. But, in spite of his vulgarity, infidelities, lies, and bankruptcies, he was, like the Persian king Cyrus of old, being hailed as the Messiah. He would free the children of Israel from bondage and exile to return to the Promised Land. He would “make America great again,” when everyone could assume everyone else was Christian. “Merry Christmas” could again be the greeting, without any hedging like “Happy holidays” in case the random non-Christian person were around to take offense.

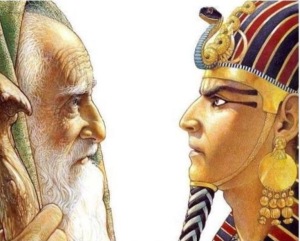

But was not the marriage of politics and religion baked into the cake from the outset? Did not Moses confront the pharaoh, demanding that he “let my people go“? What was that if not direct political action? Did not the Hebrew prophets constantly confront the kings of Israel and Judah, criticizing them and demanding change? What is the cry “let Justice roll down water” if not a demand for political change?

And did not the earliest narrative of the life of Jesus also assume that marriage? After all, the very word gospel used to describe Jesus’ proclamation of the kingdom of God was the word commonly used in the Roman Empire for public political announcements. The gospel of Mark uses that word, as he narrates, Jesus’ initial appearance: “Now after John was arrested, Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming the good news (i.e. gospel) of God, and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near, repent, and believe in the good news.’” (Mark 1:14-15) In a time in which the Roman Empire considered itself a kingdom, Jesus announced and alternative kingdom. He could have called it, As Paul did, the “family of God“, or the “household of God“ but he didn’t. He chose the apparently intentionally provocative title “kingdom of God.” How can that be read any way other than politically?

Theologian John Howard Yoder wrote The Politics of Jesus back in the ‘70s. People have been coupling the message with political agendas for a long time. By the time I was a college student, I had begun to drift away from the right-wing conservative, evangelical moorings I had grown up with. I started reading magazines, like Sojourners and books like Chad Meyer’s’ commentary on Mark “A Political Reading of Mark‘s Story of Jesus.“ I have been well used to hearing Jesus’ political agenda, sounding, if not, Marxist, then nearly so. I read Liberation Theology and reflected on the inclusive communities of table fellowship that Jesus established, which seemed similar to the Latin American base communities Gutierrez, and others described. That left-wing embrace of Jesus’s kingdom continues, as does its counterweight on the right.

So if Jesus was political, who gets to decide which politics he would embrace in America today,? I know which side I would like him to come down on, but understanding how confirmation bias blinds a person to the data that do not agree with them makes me suspicious of my own desires.

If we were to widen the question beyond merely Jesus, the gospel, and the kingdom of God to consider more broadly religion and politics, I believe it would become clear that there’s no way out of this morass. Religion has always been hand in glove with political power from ancient Mesopotamia, where annually at the New Year’s festival, the king was reinvested with Royal Authority to rule under Babylon’s God Marduk’s authority, to the anointing of the kings of Israel, by men of God, in the name of God. Politics and religion, have always been united. In fact, the very notion that you could separate the church and the state as our American founders dreamed, is itself an historical anomaly. Every army that has ever taken, the battlefield has imagined its’ God on its’ side. And the kings who sent them into battle were happy to know that they thought so. It was not until the French Revolution* that the very notion that monarchs were not given their right to rule directly by God occurred to anyone. The apostle Paul believed that all ruling authority came from God, and Martin Luther was happy to agree with him when he instructed the princess to cut down the peasants whose poverty had driven them to revolution.

We are told that one of the reasons religion has persisted is its capacity to bind large groups together in a unity far beyond kinship lines. This is an adaptive advantage. A group bound together by a common God would certainly out perform smaller less unified groups in competition for scarce resources or territory. So, religion, harnessed to politics is an adaptive advantage to us.

But, as everyone knows, religion can also be the reason for conflict. Religiously based wars are also ancient. The ideology, or rather, theology operative in the ancient world was that your god always fought the enemies’ god in the heavens as your armies battled it out on earth. The best god won, and therefore so did the army. Constantine believed it, when he had that famous vision of the cross by which sign he could conquer. He had his men carve a cross on their shields, and they won. There is no way to count all the religious wars, the crusades, the jihads, and the endless conflicts of history. We are just a new part of an old story today.

I don’t know the way out of this. I don’t really believe there is one. God (whomever that may be) will continually be harnessed to political agendas (even if the “god” is officially denied and is named “historical inevitability” by Marxists or whomever). I just want to call it out for what it is. Have your politics; defend them, argue for them, give examples, cite evidence, and ask AI for help, but leave “god” out of it. That’s my wish. It won’t ever happen, I know.

—————————————————————————————

* After writing the above I was alerted by a reader that actually the church father Tertullian argued for the separation of church and state in the second century. His argument to the Roman Empire was that Christianity should be tolerated since no one’s religion harmed anyone. Here is the money quote:

For see, we are in agreement with you when we say that it is a fundamental human right, a privilege of nature, that every man should worship according to his own convictions. One man’s religion neither harms nor helps another man. It is assuredly no part of religion to compel religion – to which free will and not force should lead us – the sacrificial victims even being required of a willing mind. You will render no real service to your gods by compelling us to sacrifice. And so we are of opinion that the religious observance of one man profits another not at all. –Tertullian, Apologeticus, ch. 24: