Sermon for July 30, 2023 Pentecost 8A, Central Presbyterian Church, Fort Smith, AR

Matthew 13:31—46

[Jesus] put before them another parable: “The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed that someone took and sowed in his field; it is the smallest of all the seeds, but when it has grown it is the greatest of shrubs and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches.”

He told them another parable: “The kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed in with three measures of flour until all of it was leavened.”

“The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field, which someone found and hid; then in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field.

“Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a merchant in search of fine pearls; on finding one pearl of great value, he went and sold all that he had and bought it.

Did Jesus smirk? Or did he wink? Maybe; of course, we do not know.

But I think perhaps he did. At a minimum, I think he often had a hint of a grin and a twinkle in his eye as he told his parables. They often have exaggerated or absurd elements meant to get people’s attention and make them think.

For example, think of how ridiculous it would be to leave 99 sheep unattended and at the mercy of predators just to go after one lost one.

Today we are looking at a number of parables Jesus used to try to communicate what he meant by the kingdom of God. Matthew likes to call it “the kingdom of heaven” — often observant Jews avoided saying God’s name — but parallel texts in Mark and Luke show that they are one and the same.

The kingdom of heaven is not about a heavenly afterlife, it’s about God’s kingdom, which Jesus said was present here and now, for those with eyes to see it and hearts open to it.

So, back to the absurdities. Jesus said, The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed that someone took and sowed in his field… Mustard plants are weeds. No farmer would ever plant one in her field. And they don’t grow into trees, they are bushy.

So why would he say that? And why add the odd bit about birds nesting in it?

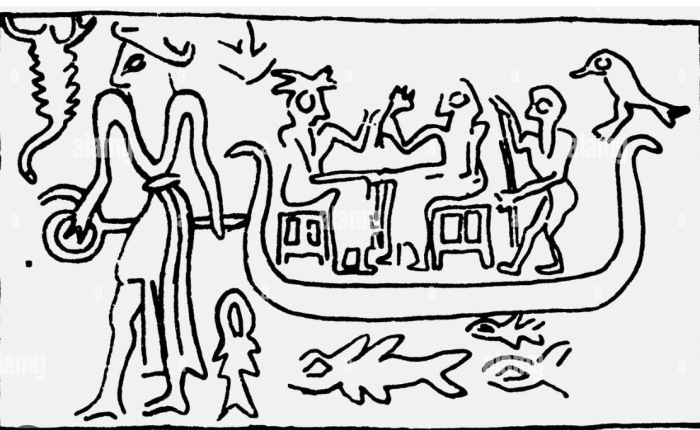

Jesus was riffing on a well-known prophecy and turning some aspects of it on its head. Ezekiel had compared the nation of Israel to a tree that God would plant back in their own land after the Babylonian exile.

So this is a tree metaphor for future national restoration. Ezekiel said:

“This is what the Sovereign God says, ‘I myself will take a shoot from the very top of a cedar and plant it; I will break off a tender sprig from its topmost shoots and plant it on a high and lofty mountain. On the mountain heights of Israel I will plant it; it will produce branches and bear fruit and become a splendid cedar. Birds of every kind will nest in it; they will find shelter in the shade of its branches.’” (Ezekiel 17:22-23)

So, that’s why the birds showed up in Jesus’ parable, to make the reference to that prophecy unmistakable. How does Jesus stand aspects of that metaphor on its head?

Because for Jesus, the kingdom of God was more like a kin-dom than a kingdom. Ezekiel’s tree was a nation. But Jesus’ was a family.

It was about relating to each other as kin. And how do you treat family? Y

ou care for each other, take responsibility for each other, have each other’s backs.

And this is hugely significant, especially for people like those Galileans who were Jesus’ first followers. All but a few were landless peasants, people overlooked, people barely making it.

So, the kin-dom of God is like getting a new family. The vision Jesus had was to start small, like mustard seeds, and then watch it grow.

It was not a national vision, like Ezekiel’s was. That part gets turned on its head. The kingdom Jesus had in mind was not a nationalist dream, it was a peasant’s dream.

But why use a mustard seed for the metaphor of small beginnings? Because, again, it was a weed. Jesus is winking.

Some people thought his moment was like a weed that needed to be eradicated. Jesus had opposition. From whom?

From the wealthy aristocrats running the temple and its banking operations in Jerusalem. We all know how that story went.

But to those who have eyes to see, the kin-dom that some wanted to eradicate has the capacity to grow up, not into a bush, but into a tree (wink, wink).

Next, Jesus says the kin-dom of God is “like yeast that a woman took and mixed in with three measures of flour until all of it was leavened.”

Again, a wink. Yeast was a symbol for corruption. At Passover, you had to remove all the yeast from your house and eat only unleavened bread.

So, again, we ask, who might have looked on Jesus kin-dom movement as something negative? The ones who were threatened by it. Remember, Jesus was teaching that people had direct access to God who loved them like a Heavenly parent without needing temples, priests, and sacrifices.

And it was not just talk. He had plans to go to Jerusalem at Passover and confront the temple administration head on.

But the kindom had the capacity to spread, like yeast in dough, and nothing was going to stop it.

His next two parables are so similar we can think about them together. The kin-dom of God is like a “treasure hidden in a field” and like a “pearl of great value.” Upon discovering it, the finder in both cases “sells all that he has” to buy it.

Is there a wink involved here too? Yes. Most of the people following Jesus were in no position to own land or pearls.

Even if they sold all they had, they could never afford either. Even a simple wooden fishing boat was a family possession for the fishermen in his company. And selling a boat would not get you land or pearls.

So who would be in a position to sell enough stuff to make those purchases? People like the young aristocrat who asked Jesus what he should do to be good with God?

Remember him? He was the one who said he had kept all the rules in the Law of Moses. Jesus said,

“If you want to be righteous, go, sell your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.” (Matthew 19:21). He wanted no part of that kind of kin-dom.

But for all those peasants who were following Jesus, they knew that they already possessed the kin-dom. Jesus told them that the kin-dom was “at hand,” “among them,” and “within them.”

And it was of inestimable value. In what way? It could turn non-persons into persons. It was open to everyone; men, women, even children, enslaved people, non-citizens, even sick and disabled people. All of them could consider themselves like found sheep, cared for by a Shepherd who would do anything to rescue them.

They gathered together around common tables where there was enough for everyone.

They learned how to forgive each other to prevent their inclusive community from becoming toxic.

They valued meekness over power and held each other’s grief and trauma histories as sacred.

They valued their communities like buried treasure.

They felt lucky to have made the discovery of life in the kin-dom of God.

Is that how we feel? We, who have nice homes, plenty of food, doctors, safe streets, and air conditioning; is the kin-dom of God a treasure?

Not for everybody. We live in a time in which there are organized efforts to create a kingdom in which everybody looks the same, speaks one language, has the same views about gender, marriage, family, and self-sufficiency.

They look at people who champion inclusion and who value difference as weeds.

They want to teach their children a version of the past that is as rosy as it is wrong: that enslaved people learned valuable skills, so maybe it was not all that bad.

That the holocaust was only about Jews and not about the five million other people that the fascists slaughtered, including gay people, and people with intellectual and physical disabilities.

If we do treasure the values of the kin-dom that Jesus taught us about, then we need to be as organized and as savvy as they.

We need to be wise as serpents, even if our goals are to be innocent as doves.

We need to believe that the arc of the moral universe does bend toward justice, but not by gravity. It bends when people actively work to bend it.

The kin-dom can grow, but only if we water it frequently. There is opposition to that vision today, just as there was in Jesus’ time.

So it is out time to do all we can, as agents of the kindom of God.

What is the alternative/. As has been said, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good people to do nothing.”